There is a popular Bible story that has fascinated me for years. It is the story of Blind Bartimeus.

His encounter with Jesus Christ is recounted in the book of Matthew in Chapter 20 from verses 29 – 30 and subsequently in Luke 18:35-43. It is a simple story that intrigues and fascinates.

Jesus and his disciples were leaving Jericho and as usual they were followed by a large crowd. As Jesus and his disciples proceeded they came across a blind beggar called Bartimeus. When he learnt that it was Jesus passing by, Bartimeus screamed at the top of his lungs , “Jesus, Son of David, have pity on me!”

The people attempted to hush him but Bartimeus screamed louder and louder until Jesus called him over and asked him what he wanted. When he said “Master I want to see,” Jesus healed him and restored his sight and Bartimeus went along with Jesus and his disciples in joy.

End of story but is it?

I remember as a 12 year old boy asking my father why the Bible recorded the man’s name as Blind Bartimeus even though he was healed at the end.

“Why is he not called “Healed Bartimeus” or “Formerly Blind Bartimeus”?”

My father had looked at me and laughed before telling me that “People like to dwell on negative things!”

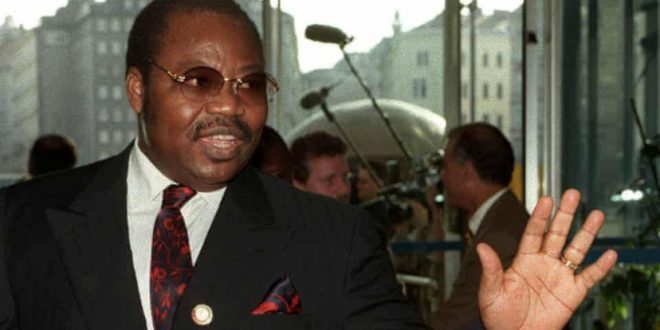

The story of blind Bartimeus came to mind when I read about Senator Dan Etete’s 80th birthday on Friday January 10, 2025.

My first thought was; oh is he still alive? And then as I read tribute after tribute, I realised that for someone who has worked in and written about Nigeria’s oil and gas industry for over 15 years, I knew very little about him.

Search on Google for Dan Etete and you are regaled with stories about an oil deal gone wrong. The impression you get is that Dan Etete‘s life began and ended with Malabu and OPL 245. It was an intriguing thought. How does one condense 80 years into one incident?

In my writings, from novels to biographies, I am keenly interested in dissecting human action and motivation; why do people do the things they do whether in a fictive universe or in business? And the first thing you learn as you go down that path is that you will have to peel off layers upon layers to find the real person because human beings are at their core chameleons.

The tributes saluted Dan Etete, the politician, technocrat and statesman who is “celebrated among the Ijaw nation as the Petroleum Minister who “championed the empowerment of indigenous players in the oil and gas sector, paving the way for greater involvement of Ijaw entrepreneurs in managing our natural resources.”

In the tributes, he is further described as a “visionary leader and one of the pioneers of Nigeria’s oil and gas industry.” They go on to note that Etete is “an untiring champion of economic empowerment for the Niger Delta people and whose tenure as oil minister laid the ground work for indigenous participation in the oil and gas sector.”

For someone who writes biographies for a living, the biggest pitfall to avoid is hagiography. Every autobiography or memoir and even an authorized biography has an agenda and the discerning writer must seek a delicate balance in order not to fall prey to the hagiographic bogeyman.

That leads us to the question; who exactly is Dan Etete? How did he emerge to become a figure of national significance? Who is this figure that seems like a conundrum ensconced in an enigma? This man about who reams of newsprint has been expended and who does not even bother to grant interviews to dispel or disprove? What sort of biographical work could emerge from a man like Dan Etete?

The man we know today as Senator Dan Etete, The Ndagbudu Keme Keni of Izon-Ibe was born Etete Dauzia on January 10, 1945. He started school in Ajegunle as a student at Christ the King School between 1955 and 1960. From Ajegunle he proceeded to Bishop Demiare Grammar School, Yenagoa from 1960 to 1964.

His career kicked off with the Nigeria Customs Service from where, after years of meritorious service, he made the leap into business. But it was not a blind leap. To prepare himself for entrepreneurship, Dan Etete took many administrative courses from renowned institutions to equip him for leadership and those would come in handy when he dipped his toe into the murky waters of politics.

He would be elected Senator of the Federal Republic of Nigeria in the 2nd republic and, recognition of his administrative and business acumen would lead to his emergence as Chairman, Senate Committee on Petroleum and Energy. He was a member of the National Constitutional conference between 1994 and 1995 before his eventual appointment as Minister of Petroleum Resources. He was in office from 1995–1998.

In their 80th birthday tribute to their son and brother, the Etete Royal Family of Odi described the former minister as “a “shining example of what it means to serve, be loyal and industrious with an unwavering commitment to unity and progress especially for the Ijaw nation.” They also go ahead to remark on what they described as his “detribalized approach to leadership” which they wrote broke “barriers, inspired hope and forged harmony within the family and across cultures.”

To return again to hagiography, is there proof of this? In a long piece published in 2019, on one of the rare occasions in which Dan Etete is quoted in the press, The Africa Report writes on Etete’s celebration of the life of former French leader Jacques Chirac whom Etete interacted with as Nigeria’s emissary during peace negotiations around the Bakassi peninsula.

Etete’s comments to The Africa Report highlight him as a statesman of note whose influence extended beyond Nigeria and whose diplomatic verve was instrumental in avoiding war with Cameroon.

The report in quoting Etete writes that thanks to Chirac’s diplomatic overtures “we avoided the worst in the late 1990s, when Nigeria and Cameroon were fighting over the sovereignty of the Bakassi Peninsula (peacefully surrendered by the former to the latter in 2008), an area rich in oil and fish. President Chirac, to whom General Abacha, then President of Nigeria, had sent me, used his influence to intervene between the two countries,” he recalls. “He made me contact the Tunisian Ben Ali, the Beninese Mathieu Kérékou, the Togolese Gnassingbé Eyadéma, and the Gabonese Omar Bongo. Informal contacts were also made at the France-Africa summit in Ouagadougou in 1996.”

It is, however, curious that whenever the Bakassi issue comes up, Etete’s name or contribution is never mentioned.

This error of omission was also apparent during his 80th birthday with the loud silence from the oil and gas sector in Nigeria which is the direct beneficiary of his time in office with his vision for indigenous participation in the oil and gas ecosystem.

The Africa Report underlines the fact with “when he was minister, he wanted to entrust marginal blocs to “indigenous” people, and develop a new class of young Nigerians “who have succeeded thanks to him”.

One significant success story, the magazine notes, is Famfa owned by one of Africa’s richest women, Folorunsho Alakija. Now, while we credit Diezani Alison-Madueke with bringing the the Local Content Act into being under Goodluck Jonathan, would we be remiss to say that without Dan Etete’s pioneering vision there would be no Local Content Act?

The marginal field regime was first mooted during Etete’s tenure under The Petroleum Act of Nigeria 1996. Paragraph 16A of the act defined Oil Marginal Fields as “such fields as the president may from time to time identify as marginal”. Eze, C. L et al writing in “Overview On The Emergence Of Marginal Oil Fields In Nigeria and Their Contribution To The Country’s Oil Production” throw some light on what constitutes a marginal field, “some oil fields are considered marginal fields based on the smallness of the reserve; they are considered too small for production to be economically viable by large multinational oil companies” before going ahead to highlight the success of the programme albeit with challenges. “By 2014, nine marginal field operators were contributing about 2.46% of Nigeria total oil production….” That growth has been exponential following subsequent bid rounds that have produced the success stories like Seplat Energy and others.

The dog-eared aphorism that a prophet is without honour in his homeland is upended in the case of Dan Etete evident, as already referenced, in the effusive tributes from his Ijaw community. A tribute signed by Hon Tariye Isaac Lelei, Executive Chairman Kolokuma/Opokuma Local Government Area, described Etete as a “passionate advocate for the rights and development of the Niger Delta.”

Another signed by Prof. Benjamin Ogele Okaba of the Ijaw National Congress saluted Dan Etete as a “foremost icon of the Ijaw struggle for self-determination” whose contributions “championed initiatives that fostered local content, paved the way for offshore exploration and advocated for the proper utilization for Nigeria’s vast natural resources.”

For the Ijaw Creek Elites, Dan Etete is a “towering icon of resilience, patriotism and industry” whose “life exemplifies the spirit of determination and excellence that defines the Ijaw people.”

If these testimonials reflect reality, the question that insists on an answer becomes, why has Dan Etete’s life and achievements been circumscribed by one incident? The answer lies in the fact that we have been presented, consistently, with a single story and a biographical exegesis may well be the means of providing a compelling and comprehensive composite of the man, the politician, technocrat and statesman.

Hottestgistnaija.com

Hottestgistnaija.com